In this post, I will show a nice, clean, organized, schematic, and theoretically well-justified approach to sorting. I’ll implement it in Python because of my target audience, but there’s no significance to the choice beyond that. I’m going to describe and implement Merge Sort and Quicksort via hylomorphisms. That may sound intimidating, but, trust me, it’s way simpler than the usual implementation. This will allow for a semi-direct comparison between the algorithms while simultaneously demonstrating some techniques which might be considered esoteric to the Pythonic mind.

First, let’s look at Merge Sort since it’s a very common example of using a hylomorphism. We will use the specification of Merge Sort to motivate our implementation of hylo. For a start, I’ll simply describe merge sort in an abstract way.

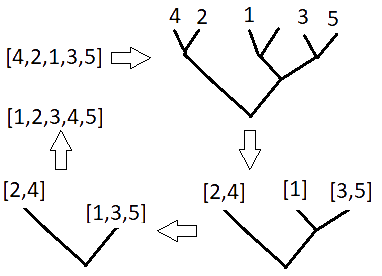

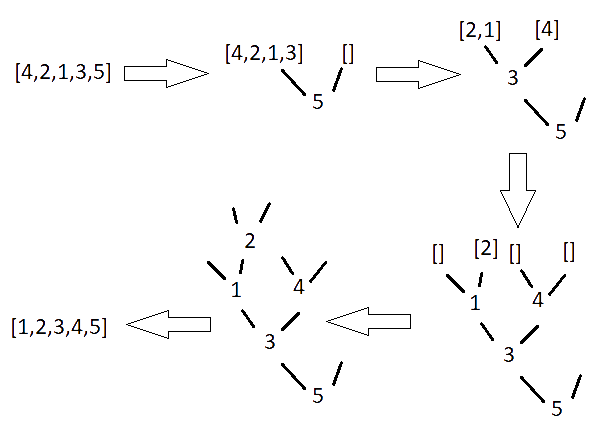

Mergesort starts by splitting a list into a binary tree, with approximately half of its components on one side and the other half on the other. These branches are then merged into lists, ensuring that the lists remain sorted at each merging. Here’s a diagram depicting the process.

We can note a few things. Firstly, the list passes through a data structure; a tree that stores data at its nodes, but the nodes may be empty. It has three constructors,

Branch(a, b), which takes two trees,aandb.Leaf(a), which holds a piece of data; in the example aboveawould be an integer.EmptyLeaf(), which holds nothing.

The tree in the example diagram would be denoted

Branch(

Branch(

Leaf(4),

Leaf(2)),

Branch(

Branch(

Leaf(1),

EmptyLeaf()),

Branch(

Leaf(3),

Leaf(5))))

Let’s implement this.

from typing import TypeVar, Generic

A = TypeVar('A')

class MaybeBinTree(Generic[A]):

pass

class Branch(MaybeBinTree[A]):

def __init__(self, a: MaybeBinTree[A], b: MaybeBinTree[A]) -> None:

self.a = a

self.b = b

def __str__(self):

return "Branch(" + str(self.a) + ", " + str(self.b) + ")"

class Leaf(MaybeBinTree[A]):

def __init__(self, a: A) -> None:

self.a = a

def __str__(self):

return "Leaf(" + str(self.a) + ")"

class EmptyLeaf(MaybeBinTree[A]):

def __init__(self) -> None:

pass

def __str__(self):

return "EmptyLeaf()"

I decided to call the tree MaybeBinTree since it’s a binary tree whose leaves maybe store data. You’ll notice that each type constructor inherits from MaybeBinTree, even though MaybeBinTree doesn’t have any data. This allows us to do some basic type checking; for instance;

isinstance(Leaf(2), MaybeBinTree)

Out: True

Though, it’s mostly for schematic completeness.

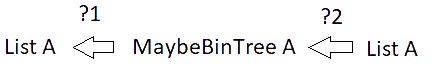

Now that we have our data structure, we want to consider what we need to make Merge Sort. In the diagram I gave, the program passes through the MaybeBinTree type. Given some As to sort, we have a function going from List A to MaybeBinTree A. We then compose this with a function from MaybeBinTree A to List A to complete the sorting.

We won’t be targeting either of those functions; instead, we’re going to go around them.

Consider that both List and MaybeBinTree are inductive datatypes. We can define List via the endofunctor ListF A := X ↦ 1 + A × X, where the 1 corresponds to the empty list, and the A × X corresponds to the case where an A is appended onto a list, called the “cons” case. This is often phrased as List A being the initial algebra of the endofunctor ListF A.

We can define this functor as follows;

L = TypeVar('L')

class ListF(Generic[A, L]):

pass

class ConsF(ListF[A, L]):

def __init__(self, a: L, a: A) -> None:

self.l = l

self.a = a

def __str__(self):

return "ConsF(" + str(self.l) + ", " + str(self.a) + ")"

class NilF(ListF[A, L]):

def __init__(self) -> None:

pass

def __str__(self):

return "NilF()"

This endofunctor allows us to define List as:

List A := ListF A (List A)

If we wanted. The canonical function from any F A to A, where A is the initial algebra, is called in, while the other direction is called out. We can define these for the list as follows;

from typing import List

def list_in(lF : ListF[A, List[A]]) -> List[A]:

if isinstance(lF, ConsF):

r = lF.l.copy()

r.append(lF.a)

return r

elif isinstance(lF, NilF):

return []

def list_out(l : List[A]) -> ListF[A, List[A]]:

if l == []:

return NilF()

else:

l2 = l.copy()

r = l2.pop()

return ConsF(l2, r)

You can note that all these do is highlight one recurse within a list;

y = [1,2,3,4,5]

x = list_out(y)

print(x)

print(list_in(x))

Out[1]: ConsF([1, 2, 3, 4], 5)

Out[2]: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

We’ll make use of these later on. We’ll also need the ones for MaybeBinTree. The endofunctor generating this datatype is MaybeBinTreeF A := X ↦ 1 + A + X × X, corresponding to the empty leaf, leaf, and branch cases. We can construct this functor as a type;

M = TypeVar('M')

class MaybeBinTreeF(Generic[A, M]):

pass

class BranchF(MaybeBinTreeF[A, M]):

def __init__(self, a: M, b: M) -> None:

self.a = a

self.b = b

def __str__(self):

return "BranchF(" + str(self.a) + ", " + str(self.b) + ")"

class LeafF(MaybeBinTreeF[A, M]):

def __init__(self, a: A) -> None:

self.a = a

def __str__(self):

return "LeafF(" + str(self.a) + ")"

class EmptyLeafF(MaybeBinTreeF[A, M]):

def __init__(self) -> None:

pass

def __str__(self):

return "EmptyLeafF()"

We can define in and out for MaybeBinTree as follows;

def maybeBinTree_in(mF : MaybeBinTreeF[A, List[A]]) -> MaybeBinTree[A]:

if isinstance(mF, BranchF):

return Branch(mF.a, mF.b)

elif isinstance(mF, LeafF):

return Leaf(mF.a)

elif isinstance(mF, EmptyLeafF):

return EmptyLeaf()

def maybeBinTree_out(m : MaybeBinTree[A]) -> MaybeBinTreeF[A, MaybeBinTree[A]]:

if isinstance(m, Branch):

return BranchF(m.a, m.b)

elif isinstance(m, Leaf):

return LeafF(m.a)

elif isinstance(m, EmptyLeaf):

return EmptyLeafF()

We can observe that this also just highlights one recurse down.

m = Branch(

Leaf(2),

Branch(

Leaf(1),

Branch(

Leaf(3),

Leaf(5))))

m = maybeBinTree_out(m)

print(m)

print(maybeBinTree_in(m))

Out[1]: BranchF(Leaf(2), Branch(Leaf(1), Branch(Leaf(3), Leaf(5))))

Out[2]: Branch(Leaf(2), Branch(Leaf(1), Branch(Leaf(3), Leaf(5))))

This is more obvious here than with the case of List; we can replace all the constructors of MaybeBinTree with those of MaybeBinTreeF and we won’t lose any information.

BranchF(

BranchF(

LeafF(4),

LeafF(2)),

BranchF(

BranchF(

LeafF(1),

EmptyLeafF()),

BranchF(

LeafF(3),

LeafF(5))))

Hence the possible definition, MaybeBinTree A := MaybeBinTreeF A (MaybeBinTree A).

The in and out functions are nice, but they aren’t as important as the fact that MaybeBinTreeF is, in fact, a functor. This means that, given a function from X to Y for any types X and Y, there’s a canonical function from MaybeBinTreeF A X to MaybeBinTreeF A Y. Since MaybeBinTreeF is just a shaped container, this function, called map, just applies that function to each of the parts containing an X.

from typing import Callable

X = TypeVar('X')

Y = TypeVar('Y')

def maybeBinTreeF_map(f: Callable[[X], Y], mF: MaybeBinTreeF[A, X])\

-> MaybeBinTreeF[A, Y]:

if isinstance(mF, BranchF):

return BranchF(f(mF.a), f(mF.b))

elif isinstance(mF, LeafF):

return LeafF(mF.a)

elif isinstance(mF, EmptyLeafF):

return EmptyLeafF()

ex1 = BranchF(2, 3)

ex2 = LeafF(2)

exf = lambda x: str(x * 5) + "!"

print( maybeBinTreeF_map(exf, ex1) )

print( maybeBinTreeF_map(exf, ex2) )

Out[1]: BranchF(10!, 15!)

Out[2]: LeafF(2)

def listF_map(f: Callable[[X], Y], lF: ListF[A, X]) -> ListF[A, Y]:

if isinstance(lF, ConsF):

return ConsF(f(lF.l), lF.a)

elif isinstance(lF, NilF):

return NilF()

ex3 = ConsF(3, 3)

print( listF_map(exf, ex3) )

Out: ConsF(15!, 3)

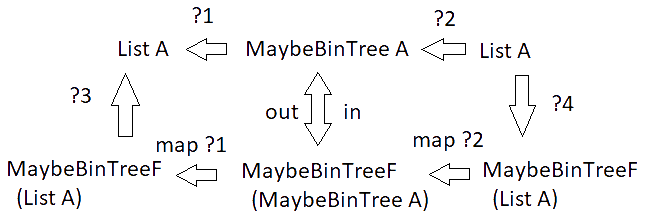

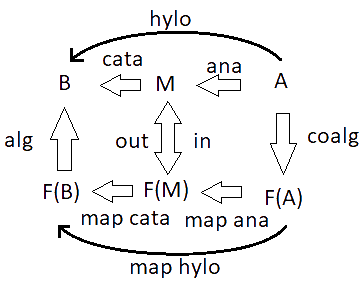

Neat! We can fill in a few details, now. We can add in and out to our diagram, along with the mapped versions of the functions we’re looking for. This also begs us to look for two more functions which we’d need to make use of those maps.

?3 and ?4 are what we’ll ultimately be targeting.

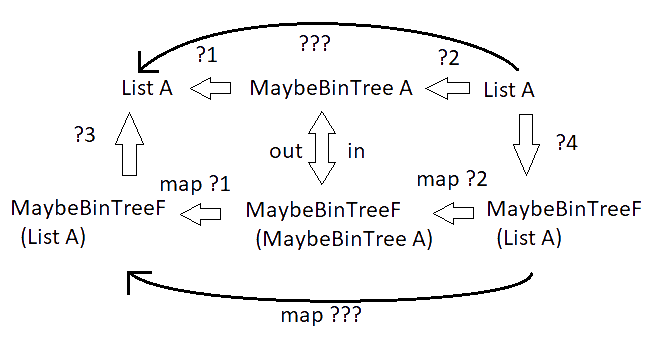

I mentioned before that we’ll go around ?1 and ?2. If we had a function pointing from our input lists to our output lists (what we were looking for in the first place), then we could map it over our lists within our maybeBinTreeF container.

If you think about this for a second, you may realize that, being under a map, ???, at the bottom, is operating one recursion step deeper then the ??? at the top is operating. This means it’s one step closer to the base case, and it should eventually terminate as a valid recursion. ??? is usually called hylo (short for hylomorphism), while ?3 is called the algebra (something that deconstructs one recursion step) and ?4 is called the coalgebra (something that constructs one recursion step). Using them as inputs, we can define hylo in general. By composing ?4 with map hylo and then ?3. The most general typing becomes clear when I clean up the above picture into something less busy;

Also, by the same reasoning as with hylo, we can derive ?1 and ?2, which are usually called ana (short for anamorphism) and cata (short for catamorphism). Incidently, those words, “ana”, “cata”, and “hylo”, are common Greek prefixes.

# Unfortunately, this is the point where Python's type system fails to capture the full generality of our program.

# We want our `F` a variable, but Python won't have it. It's type should be;

# def hylo(mapF: ..., alg: Callable[[F[B]], B], coalg: Callable[[A], F[A]], a: A) -> B:

def ana(mapF, inF, coalg, a):

return inF(mapF(lambda x: ana(mapF, inF, coalg, x), coalg(a)))

def cata(mapF, alg, outF, a):

return alg(mapF(lambda x: cata(mapF, alg, outF, x), outF(a)))

def hylo(mapF, alg, coalg, a):

return alg(mapF(lambda x: hylo(mapF, alg, coalg, x), coalg(a)))

This is all well and good; these will be the only recursive functions in our implementation. Everything else will recurse by calling one of these three. But to use any of them, we need to find an appropriate algebra and coalgebra. In the case of merge sort, our coalgebra, the thing constructing one step of our tree, isn’t a recursive function; it just splits up the list into our maybeBinTreeF container. It will take a list and split it between the branches, roughly even on each side. I’ll call it branch_split.

def branch_split(l: List[A]) -> MaybeBinTreeF[A, List[A]]:

if l == []:

return EmptyLeafF()

elif len(l) == 1:

return LeafF(l[0])

else:

s = len(l)//2

return BranchF(l[0:s], l[s:])

print(branch_split([4,2,1,3,5]))

Out: BranchF([4, 2], [1, 3, 5])

Notice that branch_split also stores an item within a leaf if it’s the only item in the list. Also notice that if we apply branch_split to smaller and smaller terms, an empty list is never actually produced. That EmptyLeafF case seems a bit pointless, but it ensures our program won’t, for example, crash if we’re asked to sort an empty list.

Our algebra, the thing deconstructing one step of our tree, will be a function that deconstructs a branch containing two lists by merging them. I’ll call it branch_merge. branch_merge will be recursive since merging is a recursive operation. That means we’ll need to define it using an ana, cata, or hylomorphism.

Alright, let’s back up. If we take the merging operation as a problem just like merge sort itself, then it starts with a pair of lists and fuses them into a single list. By taking ListF to be our recursion step, we can conceptualize this via a coalgebra which is constructing a single step of a list. If we take List to be our M and List × List to be our A in the previous diagram, then we can see how it fits into the previous scheme. The coalgebra has to be a function that takes a pair of lists and returns one of the list heads consed with a pair of lists. This head will simply be whichever of the two is biggest.

from typing import Tuple

def merging_coalg(l: Tuple[List[A], List[A]]) -> ListF[A, Tuple[List[A], List[A]]]:

l1, l2 = l

l1 = l1.copy()

l2 = l2.copy()

if l1 == [] and l2 == []:

return NilF()

elif l1 == []:

r = l2.pop()

return ConsF(([], l2), r)

elif l2 == []:

r = l1.pop()

return ConsF((l1, []), r)

elif l1[-1] >= l2[-1]:

r = l1.pop()

return ConsF((l1, l2), r)

elif l1[-1] < l2[-1]:

r = l2.pop()

return ConsF((l1, l2), r)

print(merging_coalg(([1,3,5],[2,4])))

Out: ConsF(([1, 3], [2, 4]), 5)

And the full merging function is the anamorphism derived from this coalgebra.

def merge(p: Tuple[List[A], List[A]]) -> List[A]:

return ana(listF_map, list_in, merging_coalg, p)

print(merge(([1,3,5],[2,4])))

Out: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Great! Now we can define branch_merge. All it does is merge the lists placed at the branches of the tree.

def branch_merge(mF: MaybeBinTreeF[A, List[A]]) -> List[A]:

if isinstance(mF, BranchF):

return merge((mF.a, mF.b))

elif isinstance(mF, LeafF):

return [mF.a]

elif isinstance(mF, EmptyLeafF):

return []

print(branch_merge(BranchF([2,4], [1,3,5])))

Out: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

And, with all that, we can finally define Merge Sort.

def merg_sort(l: List[A]) -> List[A]:

return hylo(maybeBinTreeF_map, branch_merge, branch_split, l)

print(merg_sort([9,4,5,3,8,0,1,2,6,7]))

Out: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

And it’s as simple as that!

Let’s move on to Quicksort. This algorithm does something quite different. It starts by splitting the list into pairs of lists which are, respectively, all less than and all greater than the head element. These splits are made over and over again, constructing a tree. After that, the tree is simply flattened. Here’s a diagram showing the process.

This, like Merge Sort, requires its own data structure. This is something I call a NodeTree, a tree that stores data at its nodes. This has the simple endofunctor X ↦ 1 + X × A × X. We don’t need the full datatype, so I’ll only define the functor.

N = TypeVar('N')

class NodeTreeF(Generic[A, N]):

pass

class NodeBranchF(NodeTreeF[A, N]):

def __init__(self, b1: N, a: A, b2: N) -> None:

self.a = a

self.b1 = b1

self.b2 = b2

def __str__(self):

return "NodeBranchF(" + str(self.b1) + ", "\

+ str(self.a) + ", "\

+ str(self.b2) + ")"

class NodeLeafF(NodeTreeF[A, N]):

def __init__(self) -> None:

pass

def __str__(self):

return "NodeLeafF()"

def nodeTreeF_map(f: Callable[[X], Y], nF: NodeTreeF[A, X]) -> NodeTreeF[A, Y]:

if isinstance(nF, NodeLeafF):

return NodeLeafF()

elif isinstance(nF, NodeBranchF):

return NodeBranchF(f(nF.b1), nF.a, f(nF.b2))

The coalgebra of Quicksort, the thing constructing a single step of our tree, will be recursive. It will take a list, and split it into a branch consisting of

- a list of elements less than the head of the list

- the head of the list

- a list of elements greater than the head of the list

I’ll call this function duel_filter. This function will recurse over the input list; deconstructing one element of the list at every step and placing it in one of the two branches. Since algebra’s deconstruct one step, we’ll try looking for that and then defining duel_filter as a catamorphism over that algebra. The algebra in question will take and a and b of type A and two lists; placing b in the first list if it’s less than or equal to a, and in the second list otherwise. The lists and a will then be placed in a branch.

def duel_filter_alg(lF: ListF[A, NodeTreeF[A, List[A]]]) -> NodeTreeF[A, List[A]]:

if isinstance(lF, ConsF):

if isinstance(lF.l, NodeLeafF):

return NodeBranchF([], lF.a, [])

elif isinstance(lF.l, NodeBranchF):

a = lF.l.a

l1 = lF.l.b1

l2 = lF.l.b2

if lF.a <= a:

l1p = l1.copy()

l1p.append(lF.a)

return NodeBranchF(l1p, a, l2)

elif lF.a > a:

l2p = l2.copy()

l2p.append(lF.a)

return NodeBranchF(l1, a, l2p)

elif isinstance(lF, NilF):

return NodeLeafF()

print( duel_filter_alg(ConsF(NodeBranchF([1], 3, [5,4]), 2)) )

Out: NodeBranchF([1, 2], 3, [5, 4])

def duel_filter(l: List[A]) -> NodeTreeF[A, List[A]]:

return cata(listF_map, duel_filter_alg, list_out, l)

print(duel_filter([4,2,1,5,3]))

Out: NodeBranchF([2, 1, 3], 4, [5])

That will act as the coalgebra for our Quicksort hylomorphism. The algebra, the thing deconstructing a single step of our tree, simply sandwiches the element at a node of our tree between the lists on its sides.

def nodeTree_flatten(nF: NodeTreeF[A, List[A]]) -> List[A]:

if isinstance(nF, NodeLeafF):

return []

elif isinstance(nF, NodeBranchF):

return nF.b1 + [nF.a] + nF.b2

And, finally, we have Quicksort!

def Quicksort(l: List[A]) -> List[A]:

return hylo(nodeTreeF_map, nodeTree_flatten, duel_filter, l)

print(Quicksort([9,4,5,3,8,0,1,2,6,7]))

Out: [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Well, it doesn’t sort the elements in place. This implementation leaves some things to be desired, as far as efficiency is concerned. IMO, this is mostly a compiler issue. Some modern languages (e.g. Formality and Idris 2) can check linearity, that data isn’t copied, only manipulated or deleted, allowing the final, compiled program to manipulate data on such calls in-place. But there’s probably a way to get this working more efficiently in Python, but I don’t care enough to do so.

At this point, you may be asking yourself, “is this really the easy way to sort lists recursively? This all seems abstract and confusing.” I would say there’s a tradeoff one has to make when it comes to making things simple. Most tasks that programmers do are special cases of very generic activities. Everything arises out of an adjunction, or a fibration, etc. We can make things very simple by climbing the tower of abstraction, but the tradeoff is that our most commonly used functions will become ever more abstruse. For my money, I think the cost is worth it. The alternative is to stay grounded at the bottom of the tower of abstraction; forever dwelling on miscellaneous details, even when they could be ignored.

As a practical demonstration, I’ll point out that all the code written in this post ran the first time, without any modification… Well, that’s not quite true. duel_filter_alg didn’t work at first because of an indentation error, but that was genuinely it. There were no errors related to recursion at all. It just worked. Compared to usual Python development, that’s quite spectacular. This general approach, called “Recursion Schemes”, is a very, very good organizational principle for recursive programs. If you want to learn more, this presentation is a very nice starting point which points to further resources.